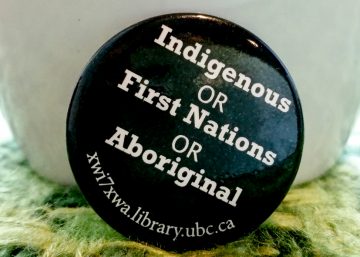

Boolean search terms: Indigenous OR First Nations OR Aboriginal. Pin provided by Xwi7xwa Library. Photo by Janey Lew.

We are changing our team name from Aboriginal Initiatives to Indigenous Initiatives. This change reflects current shifts in the politics of representation and language relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada. As we evolve in our work and listen and respond to the conversations we are engaged in, we would like to take this opportunity to share what we have been learning recently about terminologies and why they matter.

Terminology, language and naming are vital parts of developing a comprehensive understanding of who we are and how we relate to one another. In our experience, terminology can also be a source of tension, stress and anxiety because many people hesitate to engage in discussions about Indigenous issues out of a fear of saying the wrong thing or the wrong term. In our work at CTLT we draw on resources that thoughtfully unpack and open up this discussion, such as Indigenous Foundations and the sections; “So, which term do I use?” and “Why does terminology matter?”1

In order to understand the significance and complexities of language, terminology, and naming, it is important to know a little about Canadian history and the relationship between the federal government and Indigenous peoples. In 1982, the word Aboriginal was added to the Canadian constitution. Prior to this, the term Indian was used in legal contexts and referred to the identity of a First Nations person who is registered under the Indian Act2. Because of the paternalistic colonial connotations associated with the term Indian, it has fallen out of favour in popular discourse and everyday conversations. However, in certain contexts the term is still used by communities such as the Musqueam Indian band and referenced in the U.S. through terms such as Native Indian and American Indian.

The adoption of the term Aboriginal into everyday language was gradual, and not everyone has been comfortable using this term that was largely constructed and adopted through through the lens of the Canadian government and the context of federal policy. While the term Aboriginal marks and carries the trace of a particular moment of historical struggle over Indigenous rights in Canada, it nevertheless is not a term that communities tend to use to represent themselves. For many, the broad strokes of this term and its association with a colonial structure such as the government is insulting because, like many of the actions taken by the federal government, this term disassociated communities and individuals from their lands and traditional territories. One of the underlying issues in this conversation stems from the concept of (re)claiming one’s identity, and the term Aboriginal, as a one given by the Canadian government, neglects Indigenous agency over naming and identity.

More recently there has been a noticeable shift in language used to inclusively represent the diverse groups of Indigenous communities within Canada. Some believe that this began to develop momentum as a result of the United Nations adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 20073. As a term actively embraced by global Indigenous peoples in their self-representation, Indigenous has come to circulate more widely and inclusively because of its connotations of solidarity, activism, and self-definition. In several educational institutions, including UBC, you can see movement from the use of the term Aboriginal to Indigenous or the addition of the word Indigenous to existing programs such as the First Nations and Indigenous Studies Program, the Centre for Critical Indigenous Studies, the Centre for Indigenous Health, Indigenous Community Planning and the Indigenous Legal Studies program.

As a unit within UBC that is responsive to the needs of the communities we serve, as well as to the historical and geographical location we occupy, we have decided to shift our team name to be more reflective of the time and place we are in. We also recognize that in doing this we are mobile and agile in our ability to make changes in the future as the language, terminology, and legal contexts shift and become more representative of where we are and where we go with our relations.

1 Terminology. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2016, from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/identity/terminology.html

2 Ibid

3 Indigenous versus Aboriginal, which one to use? – APTN National NewsAPTN National News. (2015, February 19). Retrieved from http://aptn.ca/news/2015/02/19/indigenous-versus-aboriginal-one-use/