At the workshop More Than Content: Working Critically with Fear, Guilt, Privilege, and other “Hidden” Issues, Dr. Coll Thrush and Natalie Baloy discussed with participants the best ways to navigate classroom conversations around Aboriginal topics that are often fraught with a range of emotions. The workshop, part of the Aboriginal Initiatives: Classroom Climate series, made use of personal teaching experiences and small group collaboration to produce meaningful dialogue and tangible solutions, especially relating to non-Indigenous students’ experiences dealing with material that often produces difficult emotions.

At the workshop More Than Content: Working Critically with Fear, Guilt, Privilege, and other “Hidden” Issues, Dr. Coll Thrush and Natalie Baloy discussed with participants the best ways to navigate classroom conversations around Aboriginal topics that are often fraught with a range of emotions. The workshop, part of the Aboriginal Initiatives: Classroom Climate series, made use of personal teaching experiences and small group collaboration to produce meaningful dialogue and tangible solutions, especially relating to non-Indigenous students’ experiences dealing with material that often produces difficult emotions.

Dr. Coll Thrush, an Associate Professor in the Department of History, began the session by offering a welcome in hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, the Musqueam language. Then Ms. Natalie Baloy, PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology, explained what the operative word ‘affect’ had to do with the session. Affect, she said, refers to a range of reactions a person experiences in relation to actions, words, and experiences. Affect is basically an “academic way to say ‘emotion,’” Dr. Thrush said. Engaging with affect in the classroom is a critical mechanism in successfully being able to discuss issues such as Indigenous and settler histories, relations, and identities. Although the title and description of the workshop – ‘More Than Content’ – indicates that course content may evoke emotional responses beyond the purview of course material, Ms. Baloy and Dr. Thrush argued that affect is in fact a central dimension of learning about colonialism.

In her dissertation research, Ms. Baloy examines how non-Aboriginal people relate to Aboriginal people’s historical experiences and contemporary concerns in Vancouver. In interviews with participants, she attends not only to ‘content’ like treaty rights or material inequalities, but also to the emotional narratives people share: their memories, misgivings, expectations, and anxieties about their encounters with Aboriginal people. In the classroom, Ms. Baloy and Dr. Thrush explain, how instructors engage in these sorts of topics can radically shape a student’s learning experience.

One of the goals of the workshop was to explore the role of non-Aboriginal students in the classroom and their influence on affect. In the past, the general reaction to encounters with Aboriginal issues was “how do we ‘fix’ Aboriginal people,” said Dr. Thrush. But this is beginning to shift in a meaningful way towards the response of “how does the university change?” One of the tools that helped pioneer this paradigm transformation is the project What I Learned in Class Today: Aboriginal Issues in the Classroom. It was developed in the UBC First Nations Studies Program, and expanded the reach of the conversation while producing “a lot of energy surrounding the topic,” explained Dr. Thrush. Affective student experiences have a huge impact on classroom climate, thus instructors need to be attentive to the affective dimensions of non-Aboriginal students.

Both Baloy and Thrush made it clear, as have other instructors and facilitators in the CTLT series, that the point of the workshop was not to be prescriptive. “Many people want to be told what they should do,” said Dr. Thrush, “but it is really about developing your own authenticities in your classroom. It’s about being real and honest, and sometimes crude and simplistic.” Dr. Thrush clarified that by ‘authenticities’ he didn’t mean cultural authenticity, but rather acting in a way that expresses personal values and brings an authentic voice to the classroom.

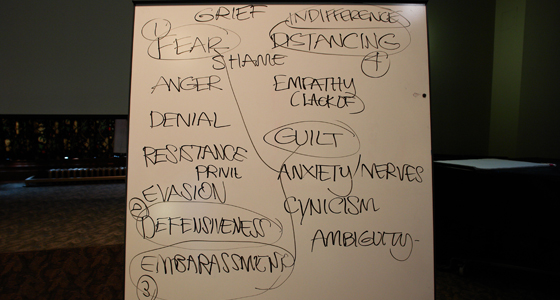

In order to develop tangible solutions for working productively with Aboriginal topics in a course, participants contributed to a list of “species” of affect that come out in the classroom and can create a precarious learning environment. Some of the suggested affective dimensions were denial, guilt, embarrassment—sometimes manifested from ignorance, and distance—, and the creation of an “us versus them” dichotomy. Evasiveness, or in its more active forms, resistance, cynicism, or resentment – what Dr. Thrush called “the colonial eye roll” – were some of the other ideas offered. Student’s indifference presents a particularly challenging affective response. Although vastly different in some ways, all of the mentioned forms of affect also have many similarities. None of them are tightly bound in expression, meaning that they can all blend into each other in some way. They “all individually or collectively lead to [emotional] paralysis,” said Dr. Thrush. The forms of affect are also all partially the result of students feeling ambiguously positioned within conversations.

In order to develop tangible solutions for working productively with Aboriginal topics in a course, participants contributed to a list of “species” of affect that come out in the classroom and can create a precarious learning environment. Some of the suggested affective dimensions were denial, guilt, embarrassment—sometimes manifested from ignorance, and distance—, and the creation of an “us versus them” dichotomy. Evasiveness, or in its more active forms, resistance, cynicism, or resentment – what Dr. Thrush called “the colonial eye roll” – were some of the other ideas offered. Student’s indifference presents a particularly challenging affective response. Although vastly different in some ways, all of the mentioned forms of affect also have many similarities. None of them are tightly bound in expression, meaning that they can all blend into each other in some way. They “all individually or collectively lead to [emotional] paralysis,” said Dr. Thrush. The forms of affect are also all partially the result of students feeling ambiguously positioned within conversations.

Ms. Baloy explained that, while planning the workshop, she and Dr. Thrush began developing their own list of “species” of affect. They were surprised by the number and range of different emotions they had witnessed in their classrooms. The exercise of collectively listing these myriad affective dimensions demonstrates the importance of recognizing the influence of affective experience on classroom climate, and learning how to address the causes and effects of these emotions.

Using this knowledge, each group of participants were given a combination of emotions and were asked to share their experiences around them. Within their small groups, participants dug deeper into their assigned set of emotional responses. Many discussed their personal teaching experiences pertaining to Aboriginal issues in the classroom, and how a teaching situation elicited the feelings they were discussing. The goal of the group work was to brainstorm concrete strategies that could be used to mitigate or handle these encounters in the future. It is often difficult for students to find a place to position themselves within the Indigenous narrative, but one participant suggested a way to discuss Aboriginal topics with emotions and opinions being “expressed without being personalized.” Dr. Thrush and Ms. Baloy suggest frontloading courses with a disclaimer. Pointing to a whiteboard that displayed all of the suggested forms of affect, Dr. Thrush said “I tell them, ‘any of you may feel x, y, or z, and that is what this class is partially about.’ Some of them self-censor and drop the course, but the ones who stay, those are the ones you want to work with. It’s not that students are expected to feel these emotions, but it’s always a possibility that they will.”

Another technique Dr. Thrush likes to use is to take a moment of silence during his class and let everyone “feel what they feel, and ask the question ‘how did we get here?’” Transparency is also another key. Dr. Thrush suggested that “it is important to acknowledge what is going on. It doesn’t do anyone any good to ignore that it’s there…Guilt, even, is very egocentric. [The response to it] is ‘I feel so bad,’ and then it becomes about that person. What it comes down to is finding a balance between acknowledging its presence and not making it all about you.” Figuring out how to do that can be a challenge.

While sharing experiences and strategies as a large group, participants debated the concept of the classroom as a “safe space.” Part of the work involved in addressing affect in the classroom may involve discomfort. Ms. Baloy asked, “when we create ‘safe spaces,’ we may ask: safe for whom?” She explained that attending to affect in the classroom may involve discomfort, especially for students who are accustomed to comfort and privilege. Participants shared their own reflections about feeling “safe” versus uncomfortable in classroom discussions, and considered ways to facilitate open and honest discussion while also challenging non-Aboriginal students to communicate respectfully when outside of their comfort zones.

While sharing experiences and strategies as a large group, participants debated the concept of the classroom as a “safe space.” Part of the work involved in addressing affect in the classroom may involve discomfort. Ms. Baloy asked, “when we create ‘safe spaces,’ we may ask: safe for whom?” She explained that attending to affect in the classroom may involve discomfort, especially for students who are accustomed to comfort and privilege. Participants shared their own reflections about feeling “safe” versus uncomfortable in classroom discussions, and considered ways to facilitate open and honest discussion while also challenging non-Aboriginal students to communicate respectfully when outside of their comfort zones.

Concluding on a more positive note, everyone was reminded that there are also positive experiences of affect. Transformation, enlightenment, and empowerment were some of the emotions on the other side of the spectrum. Dr. Thrush ended by referencing Thomas King’s The Truth of Stories, in which King points out that we can never deny that we have heard a story: “You can do what you want with the information you just received, but you cannot tell me that you didn’t hear it.” He added that sometimes it takes students years to digest and make sense of the discussions on Aboriginal topics that they have in the classroom. His own teaching experience has lent to that assertion. However, the hope is that after participating in this workshop, participants will have a better grasp of how emotions come alive in the classroom, the implications that they may have, and the ways in which they can be integrated into learning and understanding.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.